(image courtesy of clipartpanda.com)

Happy Monday, dear readers. Perhaps it’s procrastination directed at the pile of term papers sitting in front of me, but I thought I’d take a few minutes to gather ten past articles on creativity, innovation, and making a difference.

Even Shakespeare had a writing circle (2017) — “Nevertheless, it sure helps to have friends and buddies who help to prod us along in that oft-lonesome task of putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. Furthermore, if that process includes a mix of mutual encouragement, feedback, and suggestions, then the written products may be all the better for it. While the Shakespeares of the world may come around only once every thousand years or so, a supportive cohort can help to unearth the brilliance we do possess.”

What does it mean to be “onto something?” (2016) — “What does it mean to be ‘onto something’? Well, if you search ‘onto something meaning,’ you’ll get several similar explanations of the term. I like this one from Oxford Living Dictionaries: Have an idea or information that is likely to lead to an important discovery. . . . As I further acknowledged, it took me until my fifties to find that place. So if you want to be a difference maker, but you haven’t found your niche yet, try to be patient and remain open to messages and opportunities. Sooner or later, you’ll be onto something.”

Three great authors on writing to make a difference (2015) — “For fresh, inspiring outlooks on the uses of writing and scholarship to make a difference, I often listen to voices outside of mainstream academe. Here I happily gather together three individuals, Ronald Gross, Mary Pipher, and John Ohliger, whose names I have invoked previously on this blog.”

Work and solitude (2015) — “If some of the trendy gurus in work and office design are to be believed, teams and open spaces are the keys to spurring creativity and innovation. But hold on a minute, maybe this is going too far. While complete isolation and always closed doors are not advisable, the other end of the spectrum may not be such a great idea, either.”

The example of the Wright Brothers (2015) — “Their accomplishments were especially remarkable given that, as [historian David] McCullough writes, they had ‘no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own.'”

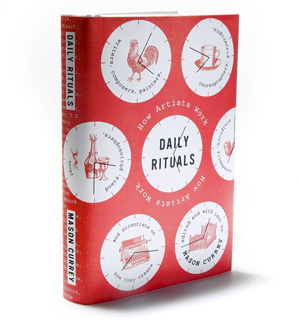

The daily routines of creative minds (2014) — “How do creative geniuses and brilliant intellectuals spend their typical workday? If you’ve ever wondered how great writers, artists, philosophers, scientists and other creators of art and knowledge greet their mornings and beyond, Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: How Artists Work (2013) is a pleasing, easy way to find out.”

Messiness and creativity (2013) — “As the photo above suggests, this may be among the most self-justifying of blog posts: A short write-up of a recent study indicating that messiness may nurture creativity.”

10 ways to make a difference: Advice for change agents (2013) — “Let’s say you’ve got a cause you care deeply about, and you want to move it forward. It may be an initiative at work, a political issue, a community concern, or something else that matters. You may be at the beginning, in the middle, or tantalizingly close to success. . . . What follows are hardly the first or last words about making a difference, but perhaps you’ll find them useful. In no particular order . . . .”

Do credibility and innovation mix? (2011) — “Is it possible to have both credibility with the Establishment and freedom to innovate? . . . [Seth Godin] summarizes the ‘paradox of success’: People with no credibility or resources rarely get the leverage they need to bring their ideas to the world. People with credibility and resources are so busy trying to hold onto them that they fail to bring their provocative ideas to the world.“

Advice to Young and Not-So-Young Folks Who Want to Make a Difference (2009) — “Several years ago I was asked to present an award to a pioneering labor leader at the annual banquet of Americans for Democratic Action, on whose board I sit. I don’t know why I thought this, but as I started to research his background, I half expected to see a long list of jobs in different labor and political organizations. Instead, I learned that he had served in his current position for well over a decade. . . . Look around you: Most of the difference makers have staying power. They are driven by heartfelt commitment and a desire to do something meaningful.”